Religion and politics in Ghana have become Siamese twins joined at the altar. Prophets, pastors, and spiritual charlatans now shape public opinion more than policies do, turning divine revelation into campaign strategy and prophecy into propaganda.

Every election season, the nation is drenched in holy oil. Political figures queue before “men of God” for televised anointings, prayer sessions, and staged vigils ceremonies designed to suggest divine approval rather than political competence. The pulpit has become the new campaign stage, and the prophet the latest political consultant.

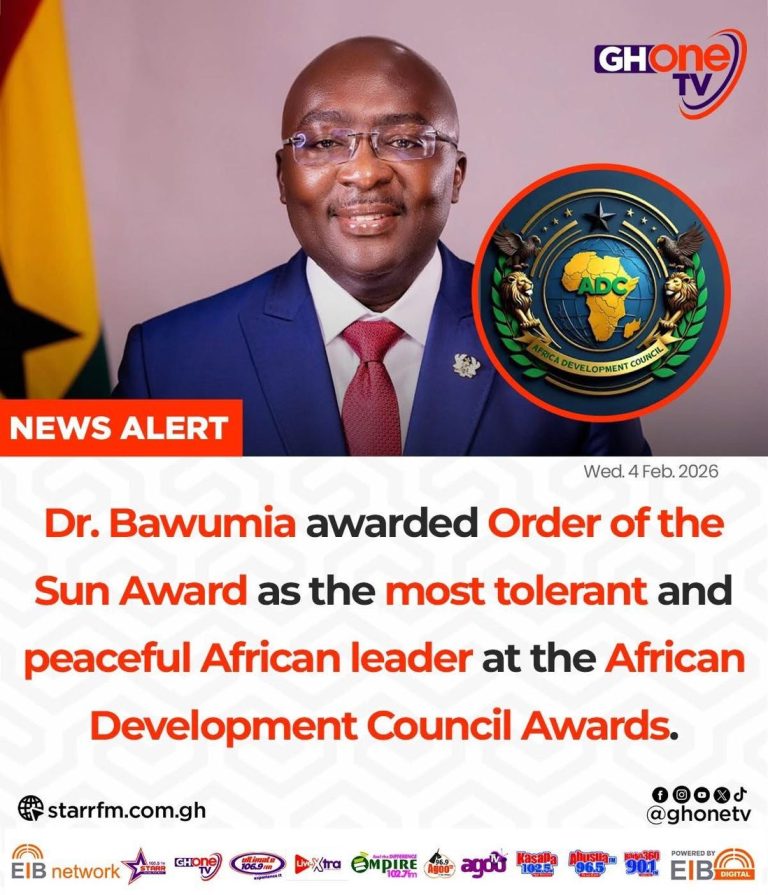

Both major parties, NPP and NDC alike, have their spiritual endorsements. “God says Mahama will win!” one declares. “The Lord has chosen Bawumia!” says another. The Almighty, it seems, votes twice in every election. Yet, when the prophecies fail, as they often do, prophets conveniently shift blame to “insufficient faith” or “demonic interference.” The faithful grumble, the politicians move on, and democracy loses another layer of credibility.

This unholy marriage of politics and prophecy erodes the rational foundations of governance. Democracy is supposed to rest on debate, evidence, and accountability — not on who can quote the loudest scripture or hire the most “powerful” prophet. When voters are told that heaven has already chosen their leader, their ballots become a meaningless ritual. Civic reasoning gives way to fatalism: If God has spoken, why should I think?

Behind the incense and theatrics lies a darker trade. Some politicians reportedly consult not just prophets but necromancers spiritualists who claim to command the dead or manipulate destinies. These shadowy rituals are whispered about in rural shrines and private chambers. Whether one believes in such forces or not, their political symbolism is dangerous: it sanctifies deceit, fear, and superstition as tools of statecraft.

The damage is subtle but deep. Public trust in institutions weakens when power is justified by “divine decree” rather than performance. National conversation shifts from policies to prophecies, from competence to charisma. And the citizen, instead of demanding accountability, becomes a passive spectator in a drama of spiritual manipulation.

Ghana is a profoundly religious nation, and faith can inspire moral governance. But when prophets become political brokers and pastors trade prayer for patronage, faith mutates into fraud. The prophet’s role should be to call out corruption, not to crown kings. Democracy withers when moral guardians become mouthpieces of power.

It is time for a spiritual detox for both politicians and their prophetic enablers. Ghana’s democracy deserves sober reflection, not sanctified manipulation. The nation’s destiny cannot be determined by who anointed whom or which prophecy trended last Sunday.

If democracy is to survive, Ghana must learn to separate the pulpit from the polling station and remind both prophets and politicians that God does not vote.

Venerable Dr Nathaniel Naate Atswele Agbo Nartey, GLOBAL GOSPEL REFORMS INT-USA