It will get me into trouble again!” laughs Ghana President John Mahama upon the conclusion of our interview.

A few weeks earlier, Mahama’s Foreign Minister had visited the U.S. State Department, only to be immediately confronted with an op-ed that his boss had written for the U.K. Guardian newspaper. In it, Mahama eruditely excoriates U.S. President Donald Trump’s baseless claims of a white genocide in South Africa and calls his “unfounded attack” on its President Cyril Ramaphosa in a fractious Oval Office meeting “an insult to all Africans.”

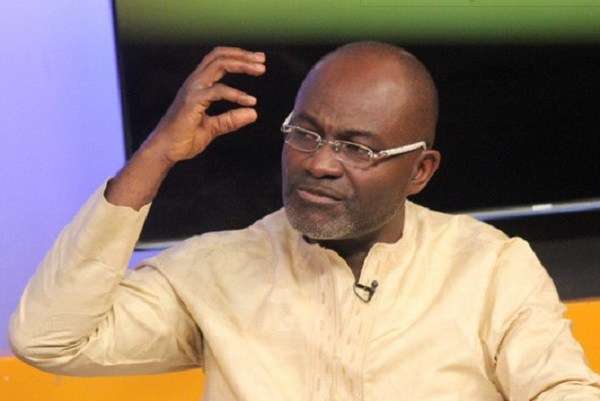

“They asked, ‘Did your President actually write this?’” Mahama tells TIME in his presidential office within Accra’s Jubilee House. “He says, ‘Yes, my President is a writer and likes to express himself.’ And they said, ‘Well, he’s President now. Can you ask him to put his pen down?’”

Even if Mahama does acquiesce and pause his writing, it’s extremely doubtful he will ever stop shooting from the hip. On Sept. 25, the 66-year-old used a speech at the U.N. General Assembly to accuse its Security Council of exercising “almost totalitarian guardianship over the rest of the world,” while demanding that an African member be added to this apex body and the abolition of its veto power. “The future is African!” he said to rapturous applause.

A little showy, sure—but far from empty talk. By the year 2050, over 25% of the world’s population is expected to hail from the African continent, including a third of those aged 15 to 24. Africa’s combined GDP was $2.6 trillion in 2020 but is projected to reach $29 trillion by 2050. Africa boasts three of the world’s 20 fastest-growing tech hubs, including first place: Nigeria’s Lagos.

But while the trajectory is indubitable, the ascent is far from smooth, as Ghana’s recent experiences neatly encapsulate. The West African nation of 34 million has long been painted as a continental success story due to its democratic and economic stability. However, Mahama was returned for a second nonconsecutive term in January with his homeland embroiled in an acute economic malaise, characterized by a huge debt burden, soaring costs, and youth unemployment at a staggering 38.8%.

In just half a year, Mahama succeeded in restoring stability—halving inflation, strengthening the national cedi currency by 30%, and embarked on a radical “Resetting Ghana” agenda. He rolled out a 24-hour economy to empower businesses and public institutions to operate around the clock, abolished onerous levies on online purchases and betting wins, and established a code of conduct for all government officials to fight corruption. He pledged to wipe fees for all first-year students in public tertiary institutions and distribute free feminine hygiene products to school-age girls nationwide. To fight joblessness, he unveiled plans to train one million coders over four years, providing the talent to bolster a nascent tech sector.

“We must improve security to make sure that the streets are safe for people to be able to go to work and come back,” says Mahama. “So we know what our responsibilities are.”

But politics is dealing with the unforeseen, and an almighty curveball was looming over the Pacific. Less than three weeks after Mahama’s Jan. 7 inauguration, the Trump Administration began gutting USAID, which had allocated $12.7 billion to sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for 0.6% of the region’s GDP.

According to the Pretoria-based Institute of Security Studies, the aid cuts could push 5.7 million more Africans into extreme poverty by next year. Meanwhile, two to four million additional Africans are likely to die annually as a result of reduced global aid budgets, estimates the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Within South Africa alone, cuts to HIV/AIDS programs could result in an additional 500,000 deaths over the next decade, reports the Desmond Tutu HIV Center.

Ghana lost $156 million allocated for HIV and AIDS control, combatting malaria, as well as research, governance, and education. Still, the cuts were “not fatal,” says Mahama. “All I did was to tell our Finance Minister to make adjustments … so we have covered it with our budget. We’re fine, but not so in some other countries. I was speaking to one of my colleague presidents and the USAID withdrawal has shut down their school feeding program. With countries like that, it will have quite a huge effect.”

School supplies

As such, Mahama’s term coincides with a new paradigm for Africa. Despite vast agricultural and mineral wealth, the continent faces limited access to global markets, unfair trading conditions, and a lack of investment. These challenges hinder economic growth, perpetuate poverty, and prevent many Africans from realizing their full potential.

The hope is that, armed with new technology, that decline of foreign aid serves a rallying call that compels African countries to forge their own paths, free from the constraints of aid dependency and external policy pressures. And while challenges persist, there are already signs that hidebound profligacy is being replaced by newfound autarky. “Ghana will manage,” says Mahama. “And it teaches us to be self-reliant.”

Mahama talks with an unruffled, languid poise that belies the candor of his words—a fitting tribune for a new era of African confidence. He was born in the small town of Damongo in Ghana’s bucolic northwest. His father was a prominent rice farmer and local MP under Ghana’s first post-colonial leader, Kwame Nkrumah. After graduating with a degree in history from the University of Ghana, Mahama taught at a secondary school before pursuing a post-graduate degree in social psychology in Moscow, graduating in 1988. His experiences amid the Soviet Union’s death throes burnished the impression that every nation must forge its own path distinct from cookie-cutter dogma. After returning to Ghana, Mahama worked for the Japanese Embassy and Plan International NGO before standing for parliament in 1996.

Mahama’s first term as president from 2012 until 2017 might best be described as underwhelming. There was a severe power crisis and a slew of corruption allegations, including the revelation that Mahama received a Ford Expedition valued at $100,000 from a contractor while serving as vice president. (A subsequent probe cleared Mahama of graft, though decreed the gift broke rules and the car was returned.) GDP dropped from 9.3% when Mahama began his term to a low of 2.1% in 2015.

By 2017, growth had recovered to 8.1% but by then voters had made up their minds not to hand Mahama a second term. Yet his successor fared even worse, plunging Ghana into an economic crisis owing to fiscal mismanagement, a lack of economic diversification, and excessive public debt from unsustainable borrowing and spending. In 2022, Ghana—the world’s sixth-biggest producer of gold and number two exporter of cocoa—defaulted on its domestic and foreign debt obligations.

It hasn’t taken long for Mahama to steady the ship—success rendered all the more impressive against the background of aid cuts. Problems with the aid culture are well-documented. While aid provided ready cash, only a tiny fraction actually went to African stakeholders themselves. USAID tried stridently to have a quarter of their budget spent through local organizations. However, the highest they ever achieved was about 10%, and last year, it actually dropped. “Western consulting companies, contractors, think tanks, NGOs, got a lot of the money that was meant to go to Africa,” says Bright Simons, head of research at the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, an Accra-based think-tank. “So Africans were never able to build capacity with this money.”

In healthy economies, citizens pay income taxes in return for public goods. Repeated studies have shown how foreign aid short-circuits this relationship, making governments accountable to donors rather than constituents, who spared the hardship of paying levies are less likely to hold officials to account. Meanwhile, the easy access to cash gnaws away at professionalism and fosters corruption. Every year, an estimated $88.6 billion—some 3.7% of Africa’s GDP—leaves the continent as illicit capital flight, according to U.N. data.

“Aid engenders laziness on the part of the African policymakers,” writes Baroness Dambisa Moyo, a Zambia-born economist in Dead Aid: Why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. “This may in part explain why, among many African leaders, there prevails a kind of insouciance, a lack of urgency, in remedying Africa’s critical woes.”

judges, or improvements on regulatory performance in African nations as these are not things that its government values at home.

Although self-reliance is Africa’s goal, the challenge is achieving true autonomy without structural transformation of nations that remain highly unproductive. Every country around the planet that has achieved structural transformation—from the Asian Tigers to the Balkans—has relied on large injections of foreign capital. Because when the status quo in sub-Saharan Africa is so unsatisfactory—with substandard education, healthcare, security, and so on—these tend to be the focus of domestic resources. Consequently, the bulk of future-focused projects are funded by donor agencies: green transition, incorporating AI, youth leadership, media literacy.

In Ghana, for instance, USAID was a big investor in eco-tourism—attracting foreign visitors to nature sites to provide alternative livelihoods, so people will move away from illegal mining. “So even though the overall amount of aid is small, when you remove it you create a very big gap in that future-rented segment of the country’s structural transformation,” says Simons of IMANI. “The future does not often appear as essential because we are so focused on the present. But the present cannot take us anywhere.”

The issue is how to inject capital without falling prey to some of the pitfalls of aid dependency. With commodity prices at record highs, Africa’s natural resource endowments are among the first areas to receive attention. And freed from the client-benefactor relationship that aid engenders, African nations are insisting upon local processing and refining to retain more of the downstream benefits.

alternative finance remains a problem. While self-financing is the ultimate goal, it will be a long road. African nations collectively possess only 20 sovereign wealth funds with a capitalization of $97.3 billion—less than 1% of the global total.

Compounding issues, many African countries pay four times more interest on their debt than high-income nations despite often having lower debt-to-GDP ratios. As a result, an average African government spends 18% of all state revenue on interest alone, according to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), compared to 3% for E.U. nations.

The TBI has proposed a new cost-efficient $100 billion debt-swap facility administered by multilateral development banks to essentially consolidate and refinance existing liabilities at concessional rates. Kenya, for one, is servicing an international loan of $1.5 billion at 9.5% interest. Refinancing at 3% would save $97.5 million annually.

Of course, $97.5 million is a colossal amount that could be used to fund schools, hospitals, and key infrastructure. Still, it is less than half the $225 million Kenya was due to receive from USAID, of which half in turn was due to be spent on healthcare. The U.S. is not the only country to slash aid—the U.K. is cutting its aid spending from 0.7% of GDP pre-pandemic to 0.3% by 2027—though the manner that USAID was atomized combined with steep tariffs still leaves a nasty taste for Mahama.

“Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve had a world that has been more interdependent and has dealt with international relations in a multilateral fashion,” he says. “Things are changing now. It looks like unilateralism has become the order. But it does not help anybody because the world progresses together.”

“Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve had a world that has been more interdependent and has dealt with international relations in a multilateral fashion,” he says. “Things are changing now. It looks like unilateralism has become the order. But it does not help anybody because the world progresses together.” Source: TIME MAGAZINE